PORT OF LONG BEACH CELEBRATES 110 YEARS OF SERVICE

The Port of Long Beach was founded 110 years ago today – June 24, 1911. According to the port’s website, it was “a wild dream scratched out of 800 acres of mudflats at the mouth of the Los Angeles River.”

An aerial view of the Port of Long Beach. (Photo: Port of Long Beach)

Since then, the port has grown significantly; it is the second-busiest container port in the United States, trailing only the Port of Los Angeles, which it adjoins in San Pedro Bay.

Today, the Port of Long Beach encompasses more than 7,600 acres of “state-of-the-art cargo terminals, roadways, bridges, rail yards and shipping channels.” It has 25 miles of waterfront in the city of Long Beach and is also known as the Harbor Department of the City of Long Beach. The port is located less than two miles southwest of downtown Long Beach and approximately 25 miles south of downtown Los Angeles.

Numerous articles in FreightWaves and American Shipper have detailed the congestion that began earlier this year at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach and has since spread to numerous U.S. ports. As one of the world’s busiest seaports, the Port of Long Beach “continued its unprecedented streak of single-month records in May by moving more than 900,000 cargo containers for the first time in its 110-year history.” The 907,216 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) processed in May broke the port’s previous record (set in March 2021) by nearly 67,000 TEUs.

Like other West Coast ports it is a major gateway for US-Asian trade. The port generates approximately $100 billion in trade and employs (directly/indirectly) more than 316,000 people in Southern California.

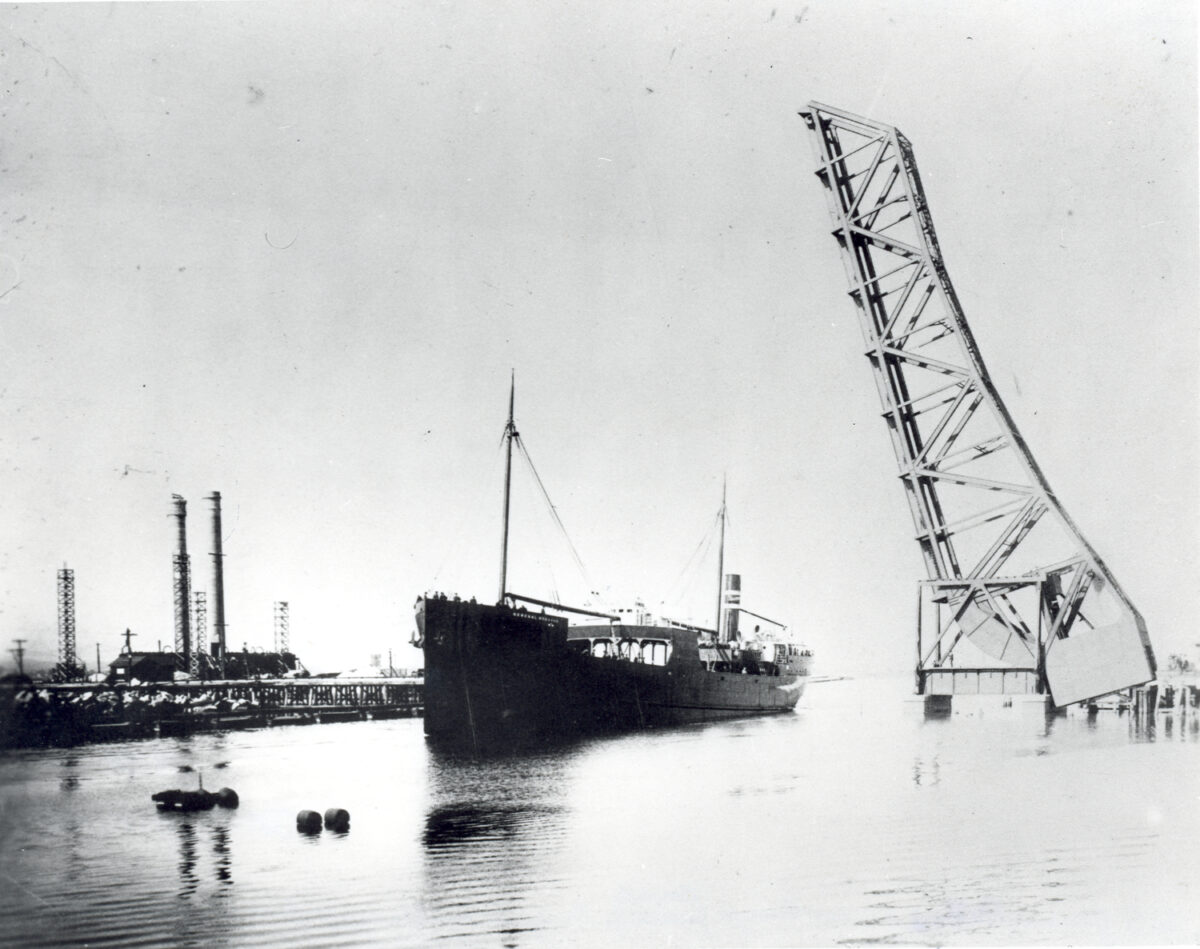

The General Hubbard sails out of Long Beach Harbor under the jack-knife bridge sometime in the 1910s. The ship was the first steel-hulled ship built at the port. (Photo: Port of Long Beach)

Early history

As outlined in the earlier FreightWaves Classics article about the Port of Los Angeles, there was a political battle in the 1890s over where the port would be located – in the San Pedro Bay area south of Los Angeles (and adjacent to Long Beach) or in Santa Monica Bay, which is west of downtown Los Angeles. In 1897 San Pedro Bay was selected by the federal government, which led to the development of the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach.

Construction of the San Pedro Breakwater began in 1899; over time it was expanded to protect the current site of the Port of Long Beach.

In October 1905 the Los Angeles Dock and Terminal Co. began the development of Long Beach Harbor. It bought 800 acres of slough and salt marshes; this area later became the port’s inner harbor.

Construction began on the Craig Shipyard in the inner harbor in 1907. This was the first industrial site in the port. Perhaps more importantly, the company was awarded a contract to dredge a channel from the ocean to the inner harbor.

In 1908 work began to dredge the Cerritos Channel, which connected the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles. The sandbar between the Pacific Ocean and the San Gabriel River washed out at high tide on June 30, 1909. This created the ocean entrance to the inner harbor.

A critical event occurred in 1911 when the State of California granted the tidelands areas in and adjacent to the port to the City of Long Beach for port operations. “Tidelands are defined as those lands and water areas along the coast of the Pacific Ocean seaward of the ordinary high tide line to a distance of three miles.”

The tidelands grant is made “in trust for the people of the State.” The Tidelands Trust restricted the use of the tidelands, as well as the use of revenue “generated from businesses and activities conducted on the tidelands.” Under the terms of the trust, the tidelands and tidelands revenues “must be used for purposes related to harbor commerce, navigation, marine recreation and fisheries.”

The first official use of the port took place on June 2, 1911 when the S.S. Iaqua offloaded 280,000 feet of lumber at the Municipal Pier. Just over three weeks later (June 24, 1911) the Port of Long Beach was officially dedicated.

The first Board of Harbor Commissioners was formed in 1917 to supervise harbor operations. And thanks to a booming economy in 1924, voters in the city of Long Beach approved a $5 million bond to improve the inner and outer harbor.

An aerial view of the Port in 1926 (although it is labeled 1929). (Photo: Port of Long Beach)

Within two years (1926) more than one million tons of cargo were handled at the port. This led to the construction of additional piers to accommodate the port’s growth.

Oil was discovered in Long Beach on and around Signal Hill in 1921. Then in 1932 the fourth-largest oil field in the nation – Wilmington Oil Field – was discovered; much of this field was underneath the city and harbor area of Long Beach. Hundreds of oil wells in the Wilmington Oil Field provided revenue to the city and port. Geologists and oil company employees determined that the oil field extended into the harbor in 1937. The first offshore oil well in the harbor began pumping oil the following year.

The discovery of oil led to increased revenue for the city and the port, but also began decades of legal wrangling over who controlled the revenue. The financial boon also led to the expansion of the port – primarily to accommodate oil tankers that carried oil to international markets (because the oil pumped from the greater Los Angeles basin had caused a glut in the U.S.).

In 1926, the Port of Long Beach gained “deep water” port status. That year 821 ships called at the port; more than 1 million tons of cargo were handled.

The Federal River and Harbor Act was passed by Congress in 1930 and became law. It authorized the expansion of the San Pedro Bay breakwater by 3.5 miles. Construction began in 1940; however, work was stopped in 1943 due to the war. Construction resumed in 1946 and was completed in 1949. At that time the breakwater ran for more than eight miles across San Pedro Bay.

The Long Beach City Charter was amended in 1931 to create a Harbor District and a Harbor Department to manage the port. In addition, a more powerful and independent Board of Harbor Commissioners was formed.

A U.S. Navy fleet is docked off Long Beach circa 1913, near the beginning of the Navy’s long history in the community.

(Photo: Port of Long Beach)

The U.S. Navy had been using the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach as a center of operations for its Pacific Fleet since 1919. In 1932 Long Beach was selected as the home port for the Pacific Fleet. As World War II raged in Europe and across Asia, the Navy bought 105 acres on Terminal Island (price – $1) for the Long Beach Naval Shipyard. Throughout World War II the port was a key area for ship construction and repair, as well as the shipment of war materiel for the U.S. and its allies fighting in the Pacific Theater. At its peak more than 16,000 men and women worked in the shipyard during the war.

A major earthquake (6.4-magnitude) struck Long Beach on March 10, 1933. More than 100 people were killed and there was damage to buildings and infrastructure across the city. The port’s infrastructure was not seriously damaged, however.

The West Coast ports suffered several months of violent labor struggles in 1934. July 5 is known as “Bloody Thursday” in San Francisco; however, in its wake longshore workers won improvements in conditions and wages. This also led to the founding of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) in 1937.

In 1939 the inner harbor was dredged again. The dredged material was used as fill to create nine new city blocks in Long Beach.

Oil wells dot the Long Beach harbor area in the late 1930s. The wells generated revenue for the City and Port but also created legal headaches and subsidence. (Photo: Port of Long Beach)

By 1943, there were 126 wells in Long Beach harbor. The wells produced 17,000 barrels of oil daily and generated $10 million of revenue annually (equivalent to more than $155 million today).

Because oil extraction leaves empty cavities, concerns regarding the gradual caving in or sinking (subsidence) of the area around the oil wells grew. The downside of oil extraction was faced again in 1945, when subsidence became a major concern in the harbor. To combat high tide flood control a number of dikes were built; geologists and engineers were engaged to develop longer-term solutions.

Following World War II, the Port of Long Beach was termed “America’s most modern port” due to the construction of the first of nine clear-span transit sheds. Piers were built and/or expanded throughout the remaining years of the 1940s.

Harbor Commissioner John Davis and Port General Manager Eloi Amar inspect a new transit shed in 1954.

(Photo: Port of Long Beach)

In 1946 a floating crane that had been seized from Germany at the end of the war began to be used at the Naval Shipyard. Nearly 50 years later (1994) it was sold to Panama and it is still in operation in the Canal Zone.

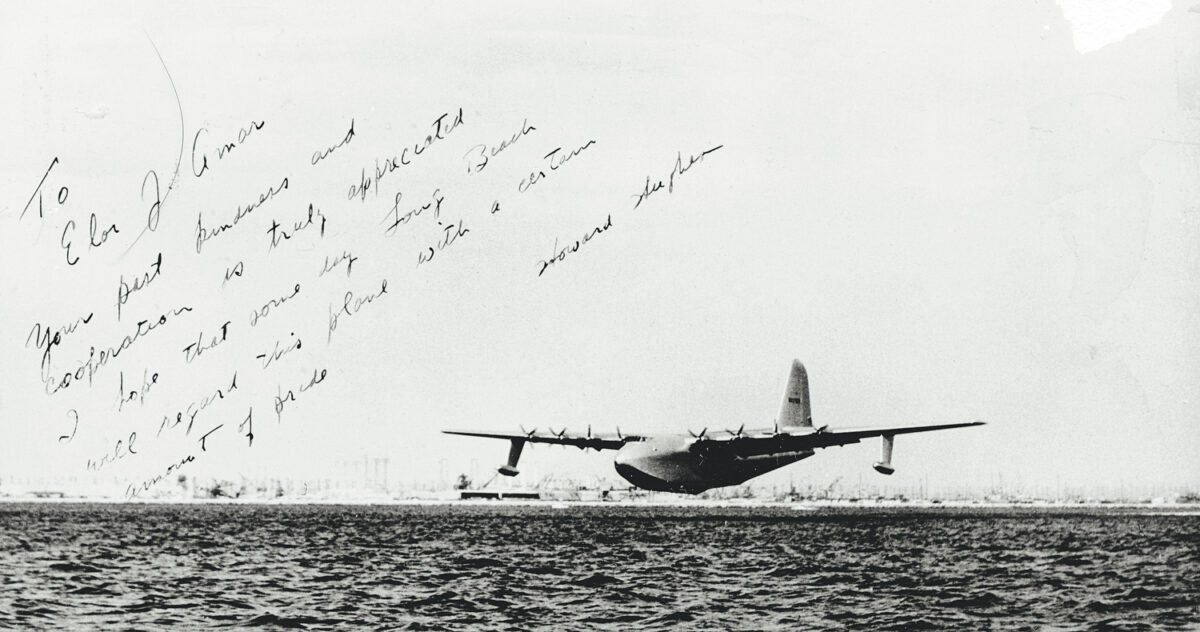

Howard Hughes’ handwritten note to Port General Manager Eloi Amar following the flight of the Spruce Goose on Nov. 2, 1947: “Your past kindness and cooperation is truly appreciated. I hope that someday Long Beach will regard this plane with a certain amount of pride.” – Howard Hughes

On November 2, 1947 Howard Hughes flew the largest airplane ever built in Long Beach harbor. The “Spruce Goose” was a seaplane that had been assembled in a hangar in Long Beach adjacent to the harbor. Its maiden flight was its only flight; it was taken back to the hangar and stayed there for more than 30 years before becoming a tourist attraction in the 1980s.

From 1948 until it closed in 1972 Pierpoint Landing was located at what is now Pier F. It became the world’s largest sportfishing operation; at its peak it attracted two million anglers annually.

In 1949 the port completed the construction of Pier E, which added 36 acres to the outer harbor. In addition, the size of Pier B was doubled.

Forty years after the 1911 Tidelands Grant occurred an amendment to the grant was passed. Its long-term impact was massive, because it authorized the use of half of the tidelands oil revenue on non-harbor projects. Two years later, in 1953, the legal argument between the federal and state and local governments regarding the owner of the tidelands and its oil revenues was settled. Federal legislation restored control of undersea lands to the coastal states.

However, in 1955 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that one-half of the oil and all natural gas revenues that were assigned to the City of Long Beach with the 1951 amendment to the Tidelands Grant would go to the State of California and not to the city. The following year state and city officials came to an agreement over the revenues from the tidelands. Long Beach paid over $120 million to the state and agreed to the Supreme Court’s division of the revenue going forward.

Sinking due to oil extraction worsened significantly in 1957. A 16-square-mile area located in the north harbor sank between 2 and 24 feet. The port spent millions to build dikes and install pumps to protect its operations. A Ford Motor Company manufacturing plant that had been located in the port since 1930 was closed due to issues related to the sinking land. More critically, the U.S. Navy warned Long Beach that its presence was threatened by the issue.

The issue of sinkage was addressed in 1960 via “Operation Big Squirt,” a program that injected water into the cavities created by the oil extraction. Subsidence was stopped due to the effort.

Malcom McLean, with a Sea-Land container above and behind him. (Photo: Maersk)

In 1962, Malcom McLean’s Sea-Land Services, a U.S.-flagged shipping company, began operations at its container terminal in Long Beach. McLean and his company had developed the concept of containerization, which revolutionized the transportation of goods via ocean, rail and truck. McLean had started the revolution at the Port of New York/New Jersey in 1956.

This photo shows construction of one of the oil islands in 1965 or 1966. Island Chaffee is nearly complete. (Photo: George Metivier)

In 1965 the port completed two additional piers (J and F). Together, they added 310 acres of landfill to Long Beach. The landfill expansion was the largest project of its kind at that time; it required 3.35 million tons of rock and 30 million cubic yards of hydraulic fill.

Oil derricks in Long Beach Harbor are hidden from mainland view through the creation of “oil islands.” The oil islands were operated by a consortium of five oil companies – Texaco, Humble, Union, Mobil and Shell. In 1967 the islands were named for NASA astronauts who died in the line of duty (Grissom, White, Chaffee and Freeman).

Also in 1967, the ocean liner Queen Mary arrived at the Port on December 10. It had sailed from Great Britain around the tip of South America (because it was too large to fit in the Panama Canal). Over the course of four years of work at the Naval Shipyard, the grand liner was moved, docked and became a hotel, museum and tourist attraction in 1971.

The Queen Mary arrives in Long Beach on December 10, 1967. (Photo: Port of Long Beach)

The Gerald Desmond Bridge opened in 1968, which connected Long Beach and Terminal Island. Several years ago it was estimated that about 15% of the nation’s waterborne container traffic was carried on the bridge.

From the 1970s to now

The port’s expansion of Pier J was finished in 1971. A 55-acre container and car import terminal, it became Toyota’s distribution center for the western United States. Container terminal construction in 1972 led the Port of Long Beach to become the largest container terminal in the nation.

Expansion brings problems; one was an increase in pollution. The port began a number of programs that were focused on preventing/controlling oil spills, improving the harbor’s sewerage system, containing debris and improving vessel traffic control. These comprehensive programs.

For its efforts, the American Association of Port Authorities awarded the Port of Long Beach its Environmental “E” Award. It was the first harbor to receive that type of award in the Western Hemisphere.

Long Beach was the first Pacific Coast seaport to earn the “E-Star” Award from the U.S. Department of Commerce for export service. The port was recognized for continued and expanded efforts that encouraged and facilitated exports.

The Port of Long Beach sent representatives to China in 1979 to discuss trade; in less than a year, the China Ocean Shipping Co. (COSCO) began sending its ships to the port. This began a successful effort by the port to forge other relationships; South Korea’s Hanjin Shipping opened a 57-acre container terminal at the port in 1991.

In 1982 the port opened a Foreign Trade Zone, which allowed duty-free manufacturing, storage, repair, testing, exhibition, assembly and labeling of products for U.S. consumption or re-export.

Tracks at the Intermodal Container Transfer Facility. (Photo: Port of Long Beach)

Located about four miles from the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, the Intermodal Container Transfer Facility (ICTF), which is operated by Southern Pacific Railroad, opened in 1987. The operating agreement for the Alameda Corridor, which is a 20-mile train and truck expressway from the ports to the Los Angeles transcontinental railyards, was signed in 1994 by the two ports and the Santa Fe (now BNSF), Southern Pacific and Union Pacific railroads.

The Alameda Corridor opened in 2002, allowing freight trains to travel from the ports to transcontinental rail yards near downtown Los Angeles quickly, without disrupting road traffic. (Photo: Port of Long Beach)

Traffic grew from the late 1990s through 2011; the port leased a number of its terminals. By 1997 the port processed approximately 1 million containers; this number more than tripled (3.3 million) by 2005. When inbound and outbound containers were both included in the port’s activities, the number of containers went from 3 million containers in 1997 to nearly 6.7 million containers in 2005.

The Naval Shipyard closed in 1997 and the U.S. Navy closed its base at the Port of Long Beach in 2001. Its property was transferred to the port.

Together, the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach are the largest generator of air pollution in metropolitan Los Angeles. Together they have implemented numerous programs to reduce pollution levels while also continuing to grow the ports’ business.

Efforts by the port to further improve its environmental footprint continued. In 2004, the port met an air pollution mandate through improved handling of petroleum coke, which is one of the port’s largest exports. This was followed in 2007 by a ban on older diesel trucks within the port’s environs. This was followed on October 1, 2011, by the Clean Trucks Program, which was launched jointly by the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles. The goal of the program was to reduce the truck fleet’s air pollution by 80% by 2012. This impacted nearly 500 trucking companies and more than 6,000 trucks that serviced the ports.

There was a strike in 2012 by the ILWU; it closed the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach for eight days. It was estimated to have cost the state of California nearly $8 billion.

The California Public Utilities Commission ruled favorably in 2020 that the construction of a fuel cell plant at the port. It is a joint venture of Toyota and FuelCell Energy; its purpose is to “produce power and hydrogen from natural gas.”

President Ronald Reagan receives a ship’s wheel during a visit to Pier G at the Port on Aug. 23, 1988, where he signed the Omnibus Trade, Competitiveness Act of 1988. (Photo: Port of Long Beach)

Economic impact

Like most ports, the Port of Long Beach is an economic engine for the city, the region and the state. Its combined import and export value is approximately $100 billion annually. The port generates jobs and tax revenue, and supports a wide range of retail and manufacturing businesses.

More than $800 million is spent annually on wholesale distribution services in Long Beach. In greater Los Angeles, the combined port operations generate more than 230,000 jobs, and more than $10 billion going to distribution services annually. In addition, the port provides about 370,000 jobs statewide and generates nearly $5.6 billion in state and local tax revenues annually.

Author’s note: As with most FreightWaves Classics articles, this profile of the Port of Long Beach is incomplete; there is simply too much information to share in one article. The article would not have been possible without the information found on the port’s website and social media pages; my thanks to the port for providing a wealth of information. Readers are encouraged to visit these sites to read more and see dozens of excellent photos and other resources.

Finally, on behalf of FreightWaves – HAPPY BIRTHDAY to the PORT OF LONG BEACH!!!

Floating crane “Herman the German” lifts the Spruce Goose as part of its move into its dome next to the Queen Mary in 1982.

(Photo: Port of Long Beach)

Source: www.freightwaves.com