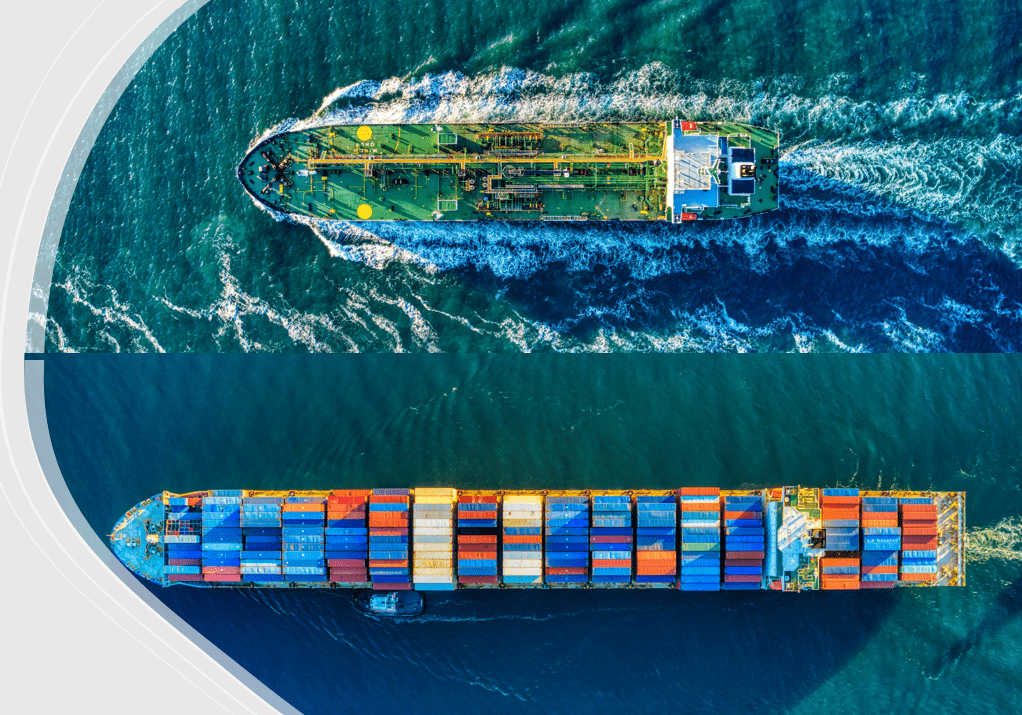

Transition to LNG driven by container and tanker sectors

The rate of construction of liquefied natural gas (LNG)-powered vessels has witnessed positive growth, while the number of ports that can refill them continues to rise.

Following the constant disruptions in supply and spike in demand, container shipping charges skyrocketed to an all-time high. Dry bulk transportation prices then climbed to rates never seen over decades. LNG shipping is now a part of the contest as well. LNG shipping charges have increased again by 40% in a single day.

What is going on in the LNG, coal, and container transportation sectors all have a nexus. Certain traditionally containerised items are now being transported by dry bulkers. China's high manufacturing capabilities, supported by US consumer demand, have contributed to dwindling Chinese energy commodity supplies, further boosting LNG carrier and bulker rates.

On the critical issue of methane slip, which has come under fire from several organisations recently, including the World Bank and the International Energy Agency, many corporate leaders came in support and asserted that the current low-pressure LNG-fueled engines can minimise methane slip by approximately 50% when compared to a first-generation low-pressure engine.

Methane (CH4) makes up the majority of liquefied natural gas. LNG emits 20-25% less downstream CO2 emissions which are sulphur-free and therefore, generate no SOx. When unburned methane is released into the atmosphere (methane slip), it has a substantial influence on climate change in comparison to CO2. Considering methane is the primary component of LNG, liquefied methane from biomass (LBG) may readily blend with LNG. The manufacture of "green" LNG and the liquefaction of natural gas to -173°C demands a significant amount of energy and storage capacity. The lack of LNG bunkering facilities for LNG-fueled ships at key ports of call throughout the world is a severe hindrance.

In addition, tankers are more likely to use LNG as fuel than bulk carriers and general dry cargo ships. On certain trade routes, LNG may be more sustainable for container ships. LNG has a lower energy density than heavy fuel oil (HFO) by 40-45%. As a result, the cost of fuel storage and containment systems in non-LNG carriers in comparison to LPG propulsion systems is higher in terms of Capital Expenditures (CAPEX).

Regulators have shifted their attention to methane emissions from ships powered by LNG, which, according to the US-based Environment Defense Fund, might jeopardise shipowners' investment in the so-called transition fuel. Methane slip is unburned fuel that is not completely burnt up in ships' engines, and its surge has been related to an increase in the number of vessels employing LNG as a primary fuel.

LNG prices are widely projected to increase even further in the months ahead. Last January, spot rates exceeded US$200,000 per day, and one voyage was booked at a record US$350,000 per day.

Source: Container News